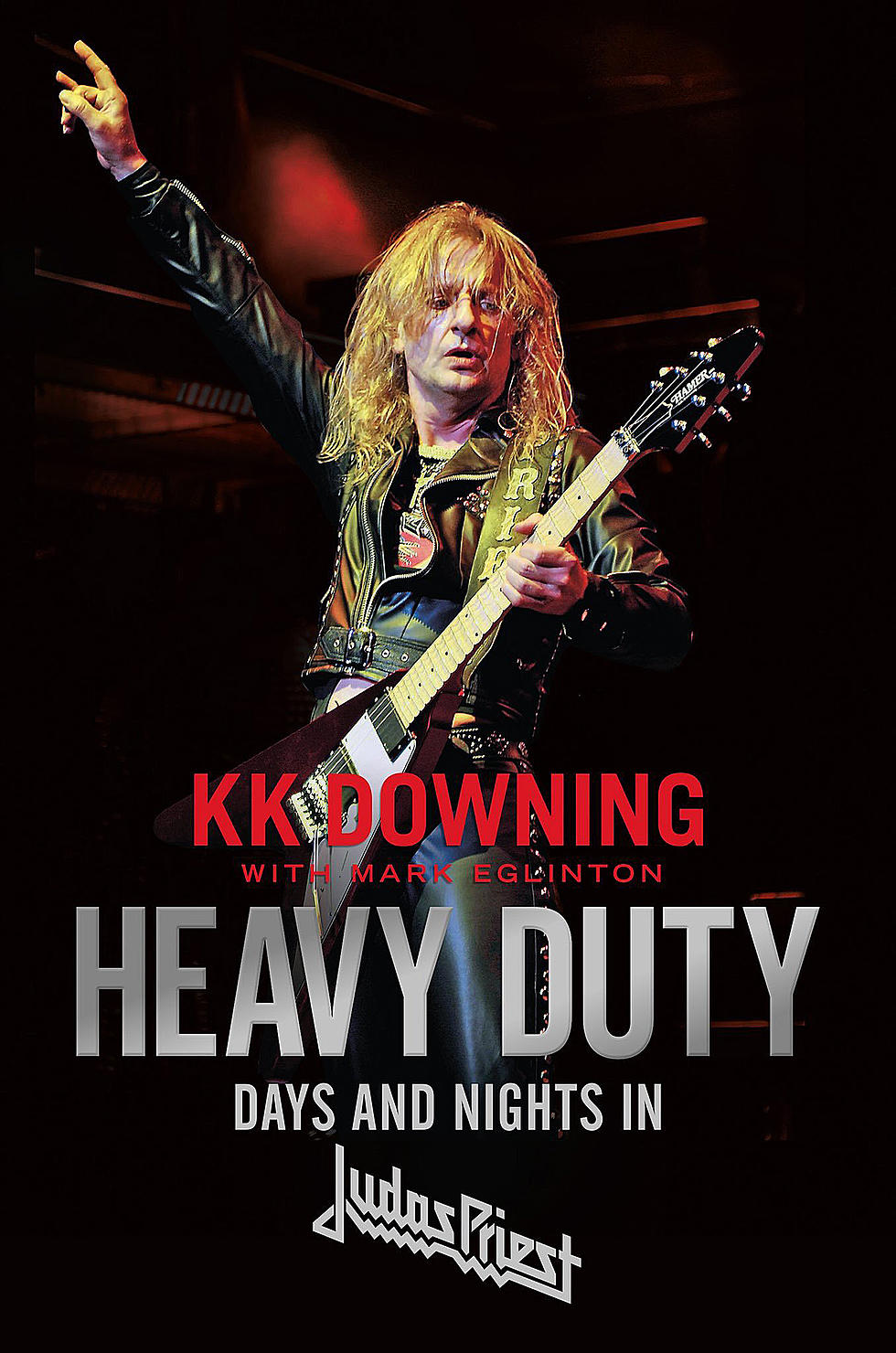

K.K. Downing – Heavy Duty: Days and Nights in Judas Priest Book Review

Judas Priest is a notoriously private band. Little has been known about the inner dynamics of the Metal Gods. Fans can now glimpse behind the scenes thanks to the new K.K. Downing autobiography.

Heavy Duty comes at a strange time in the band’s history. Exchanges in the press have revealed that K.K.’s departure was less than amicable. One can’t help but approach the book through the lens of this disharmony.

Despite the strained relations, there is no mudslinging. Each story is relayed respectfully. The intent of Heavy Duty is to portray the life of K.K. Downing, not to attack individual members of Judas Priest.

Heavy Duty explores K.K. Downing’s troubled childhood in great detail. Tales of his father’s eccentric behaviors hint at mental illness. Worse, a gambling problem coupled with staunch opposition to employment ensured the Downing family remained firmly entrenched in poverty. Downing attributes his childhood for developing a “grin and bear it” attitude that would help him endure later tensions in adult life.

Downing’s musical awakening is discussed in detail. Rather than simply state Jimi Hendrix as an influence, K.K. describes traveling to see the musician without a ticket and sneaking into gigs. That first Hendrix gig was quite memorable as he stormed the stage in a fit of manic energy. Another time K.K. wandered into a Hendrix sound check at the Albert Hall and simply sat in front of the stage. Downing was “close enough that I genuinely could smell him.” It’s precisely these intimate stories that make Heavy Duty a fascinating read.

Early incarnations of Judas Priest are discussed in detail. The origins of the name are credited to original singer Al Atkins. After joining forces with Atkins, Downing suggested that the singer keep the name of his previous band. He agreed and Judas Priest was born.

Atkins is also given credit for helping pen early Priest songs. Downing recalls writing classics like “Dreamer Deceiver” and “Never Satisfied” with Atkins, along with an early version of the epic “Victim of Changes.”

Naturally the book discusses how Rob Halford and Glen Tipton entered the band. Downing also sheds light on the seemingly endless flow of drummers that occupied the coveted drum throne.

Sometimes relocations are a bit hazy. K.K. admits he doesn’t “personally remember the precise circumstances surrounding” the departure of John Hinch. He does note that Hinch was never fired and quit the band. Possible motivations include ongoing sound issues and an argument with Glenn Tipton concerning John’s drumming.

Revelations often add new insight to established facts. It’s well known that Les Binks quit the band over a pay dispute with management. It turns out that Binks, an accomplished session drummer, had reservations about the rock star life. K.K. believes that Judas Priest’s ambition to conquer America was too much for the drummer’s humble nature. While a financial conflict was the breaking point, a personality at odds with fame encouraged Les Binks to move on.

There was much more in flux during the seventies than drummer woes. Most of the early years were spent in a confused state of curious fashion choices. Rob Halford turned up to one gig wearing “a knitted mustard-colored Harvard sweater with letters on the front!” K.K. was just as bad with his “big, white, camel-hair fedora.”

The Judas Priest appearance on Old Grey Whistle Test is cited as a perfect example. K.K.’s analysis of looking like a “hippy wizard” isn’t far off the mark. Clearly the band’s tough sound and dark subject matter didn’t match their image.

Downing started dreaming of the leather look around the recording of Stained Class. K.K. claims no discussion ever took place. Instead of voicing his ideas, he simply sought out proprietors willing to create custom-made leather outfits.

The transition from sweaters and fedoras wasn’t overnight. Downing “sensed a lack of motivation” from the band on adopting a consolidated look. Halford helped break down resistance by embracing K.K.’s leather concept.

Eventually, the rest of the band fell in line. By 1979, the iconic leather image was in place.

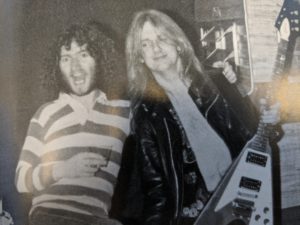

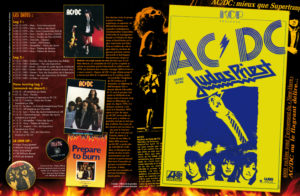

Downing also offers recollections of several tours. Some historic pairings are a rock fan’s fantasy. Judas Priest toured with U.F.O. while they were supporting Strangers in the Night. Judas Priest also toured with a Bon Scott fronted AC/DC. K.K. gushes words of admiration about Bon and his Aussie cohorts.

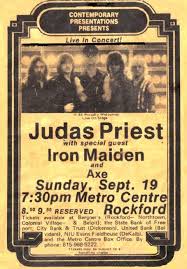

What may seem like a dream bill was actually quite an annoyance to Judas Priest. K.K. had few kind words for Iron Maiden. Paul Di’Anno set the initial tone in interviews by claiming that “Iron Maiden were going to blow the bollocks off Judas Priest every night.” In person, the young upstarts were rude, brash, and plain disrespectful. The result was an ongoing rivalry between Maiden and Priest that only escalated during later tours.

Perhaps the biggest revelation in the book is K.K.’s strained relationship with Glenn Tipton. Reality runs counter to perception. Undoubtedly, the vast majority of Judas Priest fans imagined the guitar tandem to be close friends.

K.K. does make a point to share stories of the two guitarists hanging out socially. However, in the context of band relations, we learn of a relationship tainted through ego and power struggle. Clashing ideas, uneven solo slots, and excessive drinking before shows collectively strained the partnership.

Glenn Tipton is characterized as a heavy-handed alpha male that exerts an imbalanced influence on band affairs. His cozy relationship with management allowed Tipton to control key decisions that benefit Glenn directly. Rather than risk conflict that could disrupt the success of Judas Priest, K.K. often followed an agenda that ran counter to his personal desires.

The final chapter explains his decision to quit Judas Priest. It turns out that the controlling environment created by Glenn Tipton had much to do with Downing’s desire to step down. K.K. felt compelled to write in italics when expressing the sentiment, “I’m in a bloody nine-to-five job here – and I’m still answerable to a boss!” While there were a myriad of factors that came into play, it’s clear that Tipton’s authoritative agenda was a decisive factor.

Heavy Duty is a fascinating read for Judas Priest fans. It’s disheartening to learn of the contentious atmosphere that poisoned Downing’s ability to enjoy success. One feels that the process of writing Heavy Duty was an act of catharsis. At the very least, fans now know why K.K. walked away from the band he founded.

In the years since leaving Judas Priest, K.K. has focused on running a business and worked with local bands. He has toured the world countless times and created genre-defining albums. K.K. Downing can enjoy his retirement with the knowledge that his legacy will endure.